A Question of Class

Despite some discussion relating to third class prior to the opening of the railway the entire London & Birmingham was in fact opened on the basis of first and second class. This was modelling the practice already established on the Liverpool & Manchester railway. As on that railway an initial classification of first class divided stations, trains and rolling stock. First class stations were determined by their significance as transport ‘nodes’.

First and Second Class: Stations

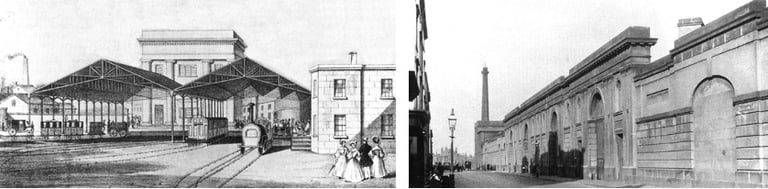

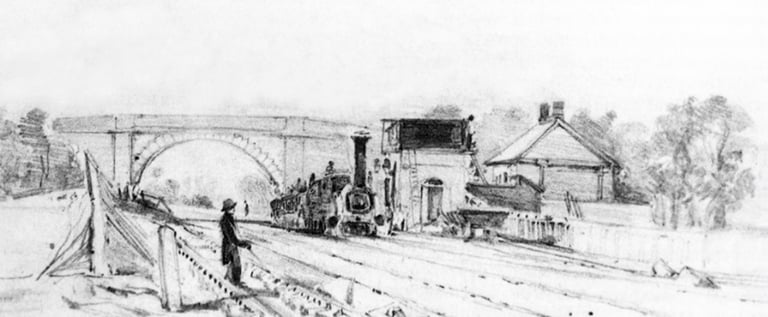

With the exception of the Euston and Curzon Street, the stations along the line in between were elegant but diminutive. Their restrictive early and primitive, the demands of mainline stations were not yet understood, designs resulted in some whole scale rebuilding, quite literally complete new station complexes at Rugby, Coventry and Wolverhampton for example, between 1838-1840. The idea of the first and second class intermediate stations effectively obsolete by 1840.

Euston: One of the first great London terminals suffered from the rapid evolution of the railway, the original design was a horrible constraint on later working, and an aborted plan to share the site with the Great Western Railway stymied the station’s evolution. Other stations would rise in significance, such as Rugby, Wolverton and Coventry, in these cases the stations of 1837 were wholly abandoned by 1840. Others would be important for some time and then go into decline such as Birmingham Curzon Street and Hamden in Arden, and others were substantially rebuilt such as Tring, Berkhampstead, and Watford after just a couple of years.

One of the factors that affected the development of the stations in the earliest years were branches and junctions. There were none initially envisaged and still none built in 1837/8. During 1839/40 however Tring, (for Aylesbury), Rugby (for the Midland Counties thus Derby and York and the North), Hamden (for the Birmingham & Derby Junction), and Curzon St. (for the Grand Junction, Birmingham & Derby Junction and Birmingham and Gloucester), would become more developed.

Curzon Street, (left), can’t be thought of as a station on its own as it shared the site with the Grand Junction Railway station (right). London & Birmingham trains going north from Birmingham went instead to the Grand Junction station and Grand Junction trains that would go to London would enter the London & Birmingham station.

First class stations weren’t exclusively for first class passengers, they served second class passengers too. Some trains only stopped at First Class stations but these included mixed class trains, as well as First Class only.

Second class stations such as Harrow, still served First class passengers on stopping or mixed trains, a term that in 1839 meant mixed passenger classes, but weren’t served by first class trains. As with Weedon and other intermediate secondary stations the facilities, at least initially, were little more than a booking office and waiting room for the passengers.

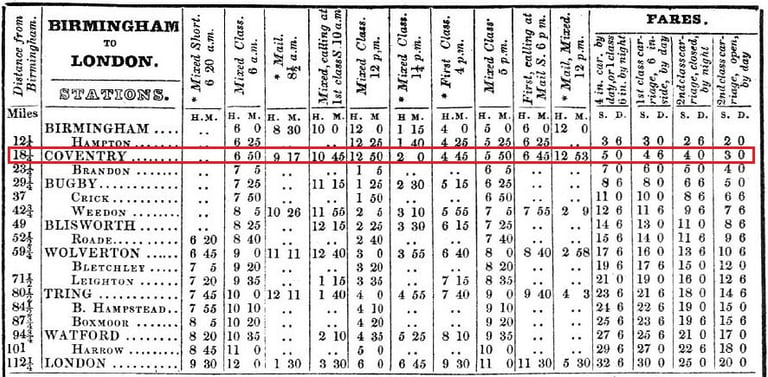

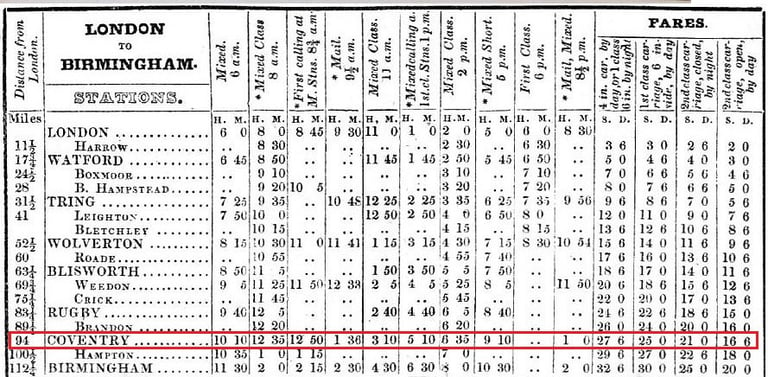

Birmingham to London timetable of 1839: Note the eight first class stations in the left hand column are in full capitals. The ten second class stations are slightly indented. Note the mixed class trains generally call at all stations but the first class (only) and mail trains only stop at the first class stations, although Weedon is preferred to Blisworth on the mails, possibly to do with connections to mail coaches to other destinations. Note that two of the mails are classified as ‘mixed’ meaning that second class carriages are included in the train even if the train only stops at first class stations.

First and Second Class: Carriages

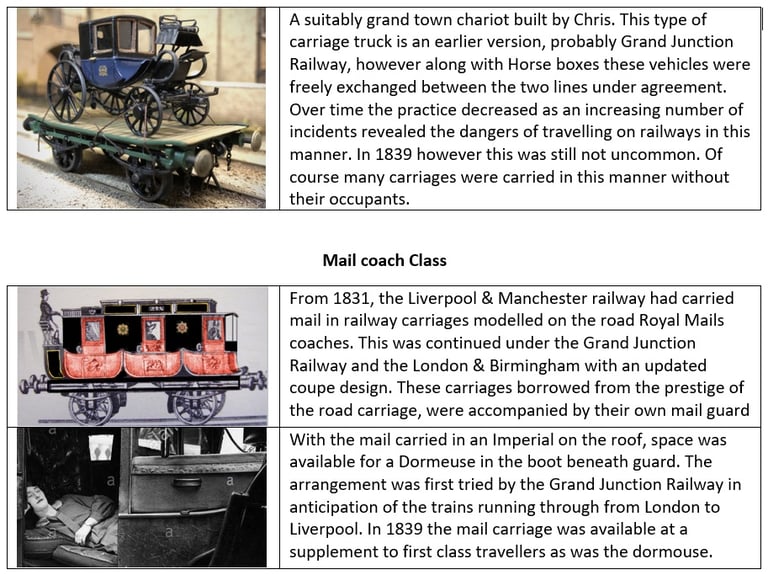

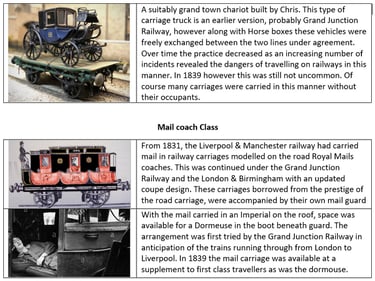

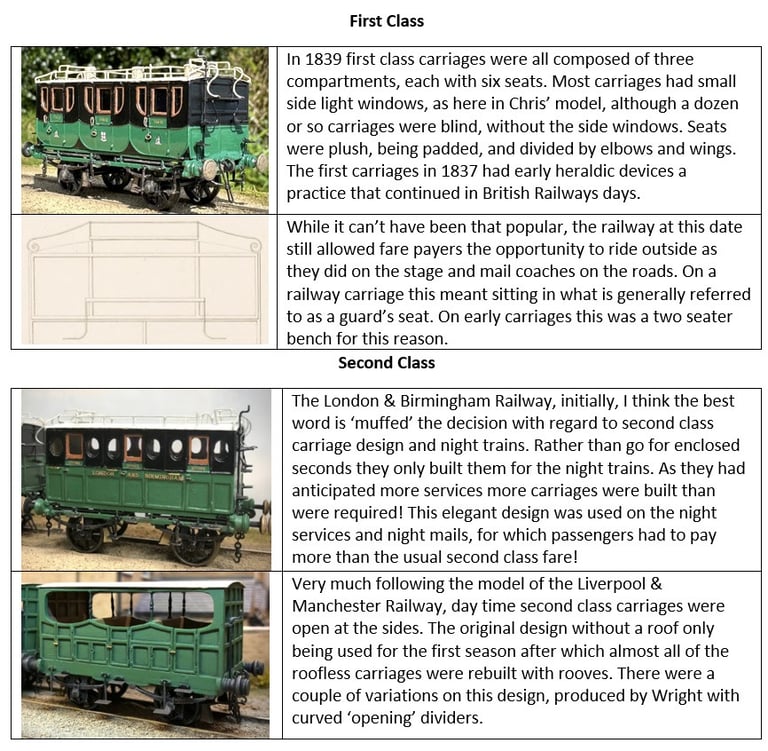

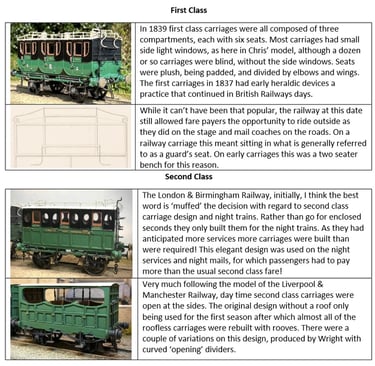

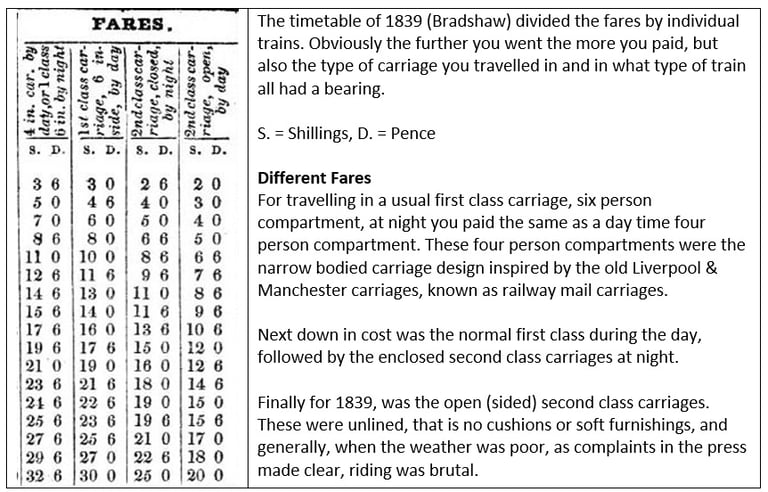

Carriages were however initially either first class or second class, third class didn’t get introduced as a fare until 1840. There were however mail coaches which were the equivalent of first class plus, more on these later. You could also ride in a first class carriage that was open at the sides but luxuriously upholstered inside.

Second class carriages were modelled initially after the Liverpool & Manchester second class open carriages or blue boxes. The mail coaches and second class enclosed carriage designs were modelled on Grand Junction practice, although the enclosed second design was rejected and replaced by Joseph Wright’s own design.

Initially there were no plans for composite carriages but these did appears later, through the need to handle smaller passenger numbers on the branches. The first composites were modifications of existing carriages. The first composite that ran on the London & Birmingham was in fact the Birmingham & Derby Junction composite that was required by the Board conduct Derby passengers to Curzon Street.

A depiction of First Class passengers from 1847 shows them well dressed and significantly few in number! First class were usually six to a compartment. Illustrated London News, 22nd May 1847.

First and Second Class: Passengers

The London & Birmingham was very much under the influence of the Liverpool Party when it came to how to operate the railway. However they did differ in terms of wanting three classes of travel, the Liverpool & Manchester only had two. In saying this both the railways operated mail coach travel as an upgrade to first class. However the London Directors initially opened the railway with only two classes of travel – they were taken with the idea that many people would travel in the first season just to see the line, they called this curiosity travelling. This is why the trains in TT Bury’s prints are long and generally of two classes of carriage.

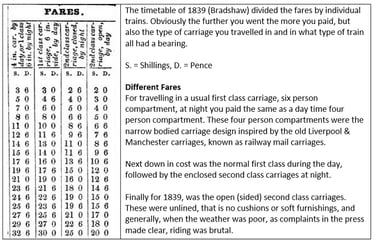

A second class carriage, note the increased number of passengers also the deliberate depicted increased unruliness. First class were usually six to a compartment and such second class carriages were usually eight. Illustrated London News, 22nd May 1847.

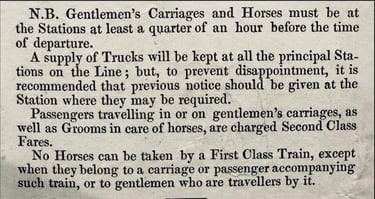

At the top end of luxurious travel you could either ride mail coach or ride in your own road coach on a carriage truck, but the problem was what to do with your servants. On some occasions male servants were required to sit outside on first class trains, this was inherited from coaching practice, ladies’ servants however could ride in the same carriage as their mistresses, on other occasions dedicated compartments were provided and eventually in 1843 a dedicated carriage was provided for them. Incidentally it seems the practice of grooms was to ride with the horses.

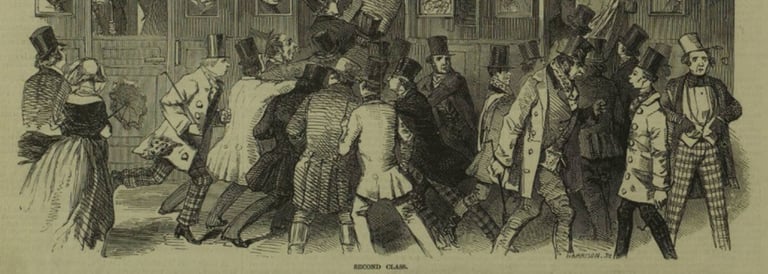

The wealthiest in society (left, Illustrated London News, 1847), generally rode in their private carriages maintaining a safe distance from the lower orders and the emerging middle classes, seen here looking on, with liveried servants. The Mail coaches (right) were grand, efficient, had privileges on the road, and were well thought of. Travelling by them was just acceptable, for the highest orders, if private carriage higher wasn’t available.

Private Carriages and Mail Coaches

Although often overlooked on the timetables, the wealthiest paid the highest fares. They often travelled with their carriages. Not always with horses as these might be hired at the destination or the owners own horses would meet the train at the station nearest the country residence.

What is least well known is that a number, but not all, of the wealthy and the aristocracy still insisted in travelling in their private carriages loaded onto carriage trucks as here in Chris’ model. Fares differed over time, riding in your carriage which meant servants travelled to, meant not only the fare for the carriage’s transportation had to be paid but also for the carriage occupants and servants.

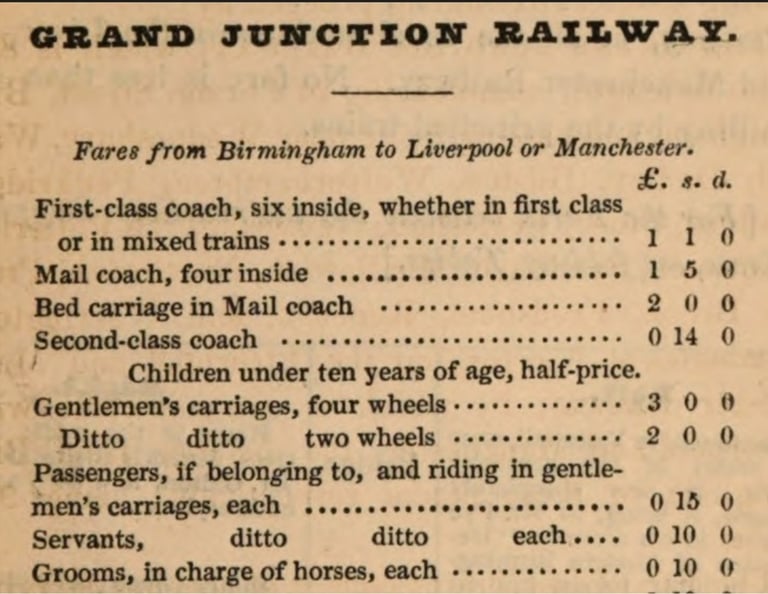

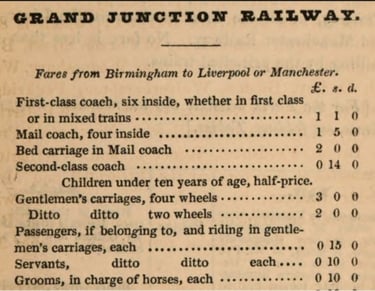

Summary of methods of travel passengers on the London & Birmingham Railway in 1839